The Great Reading Collapse

How decades of hollow instruction drained reading of its meaning—and why it’s time to start believing in our students again.

“Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.”

— Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

There is a sense of panic in the air as educators and leaders have had some time to reflect on on this year’s dreadful NAEP scores, seemingly in free-fall since the pandemic. The 74 called the results “cataclysmic” and signaled that we had a “lost generation” of students.

The trend looks even worse when you consider the accomplishments of the early 2010s. Michael J. Petrilli noted this for the Fordham Institute back in September:

But here’s an alarming fact that you probably haven’t seen before: The cohort of students who scored at record-low levels in 12th grade reading were part of the same generation of kids who scored at record-high levels in fourth grade.

Woah.

Then this week, The New York Times reported that even Harvard professors are struggling to get students to do their reading or show up for class, a trend almost certainly occurring nationwide.

The kids aren’t just skipping class; they’re opting out.

Yes, there are implications for our workforce, our national competitiveness, and our societal identity. But as a teacher who saw these kids through the most tumultuous years of the 21st century, it’s impossible not to experience a deep sense of mourning over the loss of human potential.

If you simply see the pandemic as the sole cause, then you see only a blip that doesn’t need addressing. But if you squint a little, you can see a longer thread pulling taut: years of schooling stretching into the post-pandemic era that asked students to participate in learning without ever requiring them to care about it.

The kids are flailing, and we’re to blame. So what’s the way out?

The “Reading Skills” Fallacy

Few people write more consistently or clearly than Natalie Wexler on how we have arrived here. Wexler, who authored “The Knowledge Gap” and “The Writing Revolution,” wrote this piece last week on her excellent Substack, Minding the Gap. Here, she makes the point that in the decades-long shift to teaching reading as a checklist of transferrable “skills”—finding the main idea, making inferences, identifying tone—we’ve drained texts of meaning and deprived students of the opportunity to connect with them.

It’s the academic equivalent of a workout plan made entirely of finger stretches. Useless…and mind-numbingly boring.

Wexler has always argued that comprehension doesn’t exist in the abstract — it grows out of knowledge, vocabulary, and context. But we’ve built a system that sometimes feels allergic to those things. Instead of supporting students through nuanced arguments made over the course of a complex narrative, we offer “skills practice” on passages short enough to fit on a PowerPoint slide.

If you wonder why college freshmen don’t have the stamina or desire to read and reflect on an academic paper between classes, start there.

The Vanishing Weight of Rigor

I’ve long been obsessed with this 2018 keynote by Timothy Shanahan (the whole talk is worth your time, but the stuff from minutes 12:00-26:30 hits hardest for me)

I’ll come back to this clip, as well as Shanahan’s newest book, many times, but his core point—that reading practice without the “weight” of sustained attention to complex, grade-level appropriate text ends up being hollow and, often, a waste of precious classroom time—has guided me through hundreds of lesson-planning decisions in my own classroom.

“What makes a difference in your reading is actually just how well you can read,”

- Timothy Shanahan

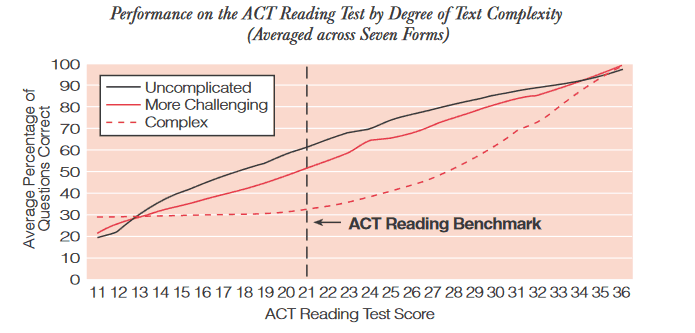

In the talk, Shanahan cites an ACT study from the early days of No Child Left Behind that centers on this chart, demonstrating how students across a range of “reading abilities” perform on simple or “more challenging” text in a predictable pattern, but fall off dramatically when attempting to answer questions about complex text.

As ACT puts it in the study, “Performance on complex texts is the clearest differentiator in reading between students who are more likely to be ready for college and those who are less likely to be ready.” Unfortunately, in our modern environment, students performing well above “benchmark” struggle when it comes to this most important skill.

Students need to strain under the weight of complexity or the “muscle” of comprehension never fully develops.

The Lost Art of Attention

I will confess that despite being a Teach Like a Champion acolyte, I’m still working my way through their newest project, “The Teach Like a Champion Guide to the Science of Reading.” But even in the first chapters, I’ve already been jarred by the urgency around their findings on the newest battleground around reading—attention itself.

The chapter that caught my eye, “Attending To Attention” is full of anecdotes and data that capture the seismic shift in student attention spans and reading patterns that are symptoms of our modern societal shifts.

In the face of the crisis, however, the authors posit that teachers actually get to shape a huge amount of the day-to-day experience, and as a result, have a major impact on (and responsibility for) shaping the habits that ultimately shape the brain chemistry of our students.

Because our brains wire how we fire, how we read consistently affects our neurological capacity for future reading. This means we can shape students’ reading experiences in classrooms, taking advantage of the social nature of reading, to develop our students into more attentive and deeper readers—and ones who enjoy it more. .

The problem today? Many teachers seem to simply believe that their students “can’t” or “won’t” so they don’t even try. Consider this anecdote:

…in an Atlantic piece on “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” a first-year student at Columbia University told her required great-books course professor that his assignments of novels to be read over the course of a week or two were challenging because “at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.

To solve this, the idea is simple: attention isn’t a finite resource but a trainable one. Classrooms, they argue, shape what students focus on and for how long. When tasks are scattershot and expectations for focus are low, we wire students to drift; when we structure lessons around deliberate attention, we wire them to think.

Attention must be taught — not expected as an act of willpower, but cultivated as a habit of mind. Without it, even the best curriculum dissolves into noise and students fail to train for the challenges and opportunities of the real world.

The Opportunity

Even as the world changes around us, the classroom conditions that drive trajectory-altering student growth have remained largely the same.

Read rich, full and complex texts

Fill knowledge gaps and supporting student comprehension

Craft unbroken chains of “flow state” time for students to be engaged with worthy tasks and text

Those ideas aren’t revolutionary. They’re just hard. They require teachers to believe that kids can handle difficulty, and leaders to believe that the training, curriculum and policy shifts are worth the time.

And those freshmen whose attention spans and achievement levels collapsed on our watch? They’re going to be furious with us, and rightfully so. We can’t let it happen again.

Let’s start believing in our kids. It’s time to expect more.

Yes! A high-quality education is a radical thing, but is built in a very boring way. An education lives or dies by the quality of the text.

We read a poem five times together in class today. Students came up with a correct, but insufficient theme after the first read. After the fifth read, students were able to articulate how the inconsistent rhyme scheme supported the author’s message that imperfection and failure are fundamental to (not obstacles to) success. When they then wrote their analytical paragraphs, they were truly excited to articulate what they had discovered. If they had written after only the second read, their responses would have been perfunctory.

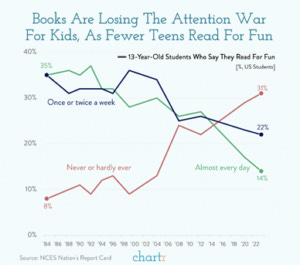

Luke, I totally agree with your main premise that drilling skills without giving kids meaty texts is boring and counterproductive to actually attaining those skills. I'm wondering how you think smartphones figure in here? I know in my own family, reading went down quite a lot when we got smartphones... we were very late adopters, and I could see the difference in myself as well as my husband and kids. This experience, having a harder time focusing on longer texts after getting a smartphone, has led me to be a big proponent of the smartphone-free schools movement.... because I think 8 hours a day without that constant distraction can help rewire kids' brains. Interested what you think!