The Surprising Power of the Humble Worksheet

Students spend hours on screens at school. It's bad for them, and paper is better anyways.

Here’s a simple fact about me—I’m a paper guy at school. The scratch of pencils, the silly doodles, the woody nubs scattered across the floor at day’s end… they do something for my soul.

But it hasn’t always been that way. When I started in the classroom, computers were decidedly in.

One upside of working in a recovering disaster zone was the influx of federal funding, and among the most popular uses of that funding was high-end laptops—an important signal that we were taking the digital age by the horns, even in rural-ish Louisiana.

The laptop cart was to be reserved at least a week in advance, but sooner was better as competition was stiff. We saved challenging lessons for laptop day, and for good reason—mundane activities like essay-drafting took on a transcendent quality when the MacBooks were involved.

To handle the “machines,” as we called them, copious paperwork was first to be submitted by parents, fingers were to be cleansed of Cheeto dust at the science sinks, and the ultimate behavioral threat loomed large over the students: loss of tech privileges.

So, with little other encouragement, students delved urgently into their work, fully in thrall to the glowing screens. And as a struggling first-year teacher, some of my only moments of true peace came on laptop days. Technology was a boon to us all.

But, as with most things we cherish, the sheen was destined to fade.

How the MacBook lost its magic

Most of the issues with school-aged kids and excessive screen time are either well-known or easy to infer. Jonathan Haidt, author of The Anxious Generation, doesn’t mince words on the topic:

“The presumption should be that anything you do digital (in schools) is worse than anything you do manual.”

And anyone who has watched an 11-year-old use a custom keystroke sequence to swipe to a hidden screen to refresh their Minecraft farm in the middle of a math lesson has a pretty good sense of what he means.

There are a lot of feelings on this topic, and I know teachers who use “machines” with prudence and care. They save time and paper, get great work out of students, and can’t imagine living any other way.

I applaud them, but that was never me, and it’s usually not the reality that I see in classrooms, either.

So what happens when we take the machines away? And what takes their place?

The secret weapon is…packets?

This is where my favorite classroom tool comes in: the structured student packet, the workhorse of middle school learning.

It’s fair to ask: how does a worksheet—almost the definition of sterility—fit into a human-centered classroom? The answer is simpler than it seems.

Packets are the staple of high-quality curriculum (Fishtank, Reading Reconsidered, Novel, and Achievement First, to name a few) and there’s good reason for that. The Teach Like a Champion team calls this “Double Planning” and writes,

“A well-designed packet gives both teacher and students everything they need for the lesson at their fingertips … Further, having a copy of the packet yourself enables you to work from the same set of materials as your students, allowing you to manage the student experience … quickly and effectively.”

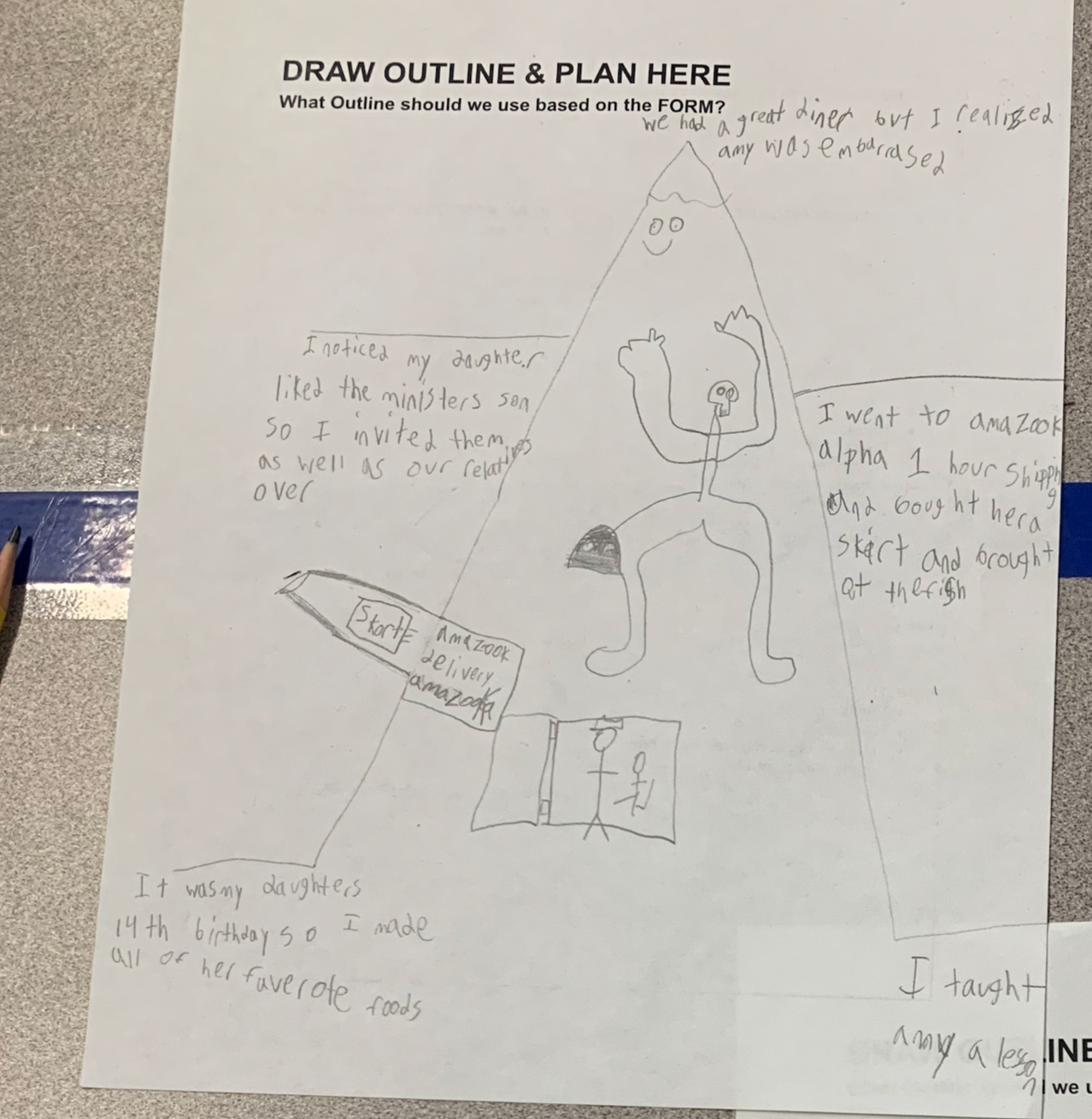

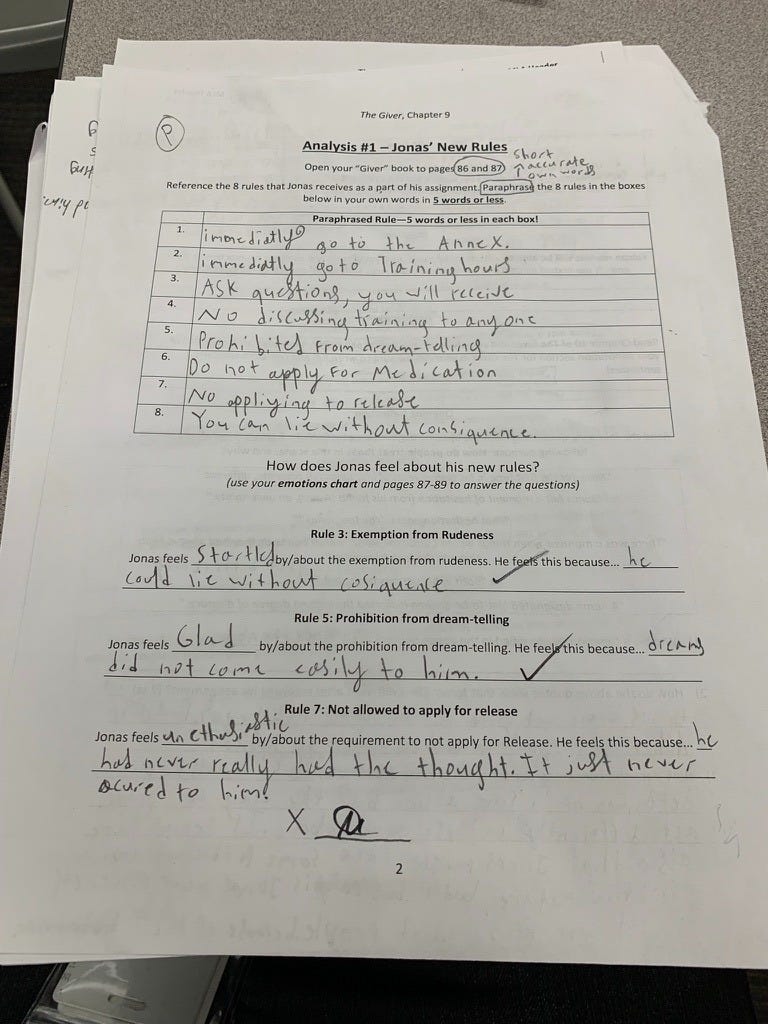

Here’s how that looks in practice. Consider the student sample below, from a lesson on “The Giver:”

It may look, well, sterile at a glance, but there are a few tricks hidden in plain sight.

The circled “P” at the top of the page indicates the “whom” in this case – “Partner Practice.”

The printed directions contain some light annotations – with my model packet on the doc cam, I circled the pages for this segment, then we all opened them together. Then, we defined key characteristics of paraphrasing together. The words, “short, accurate, own words” were written on every paper in the room, modeled again on the document camera up front.

At the bottom of the page, the “x____” was also hand-drawn by students during the activity introduction – that was the teacher-check point. And this student, having successfully met the criteria for this page with their partner, received the coveted signature indicating that they completed the work to expectation and were approved to move on.

Three things paper does that screens can’t

So let’s account for what I really have here.

1️⃣ A quick record of who’s tracking directions.

2️⃣ A built-in reason to circulate and give feedback.

3️⃣ A grading shortcut that reinforces mastery.

“Your Paper Should Match Mine” 📝

We basically never read directions without annotating them. Students might squiggle a key word, box an action, draw arrows to connect a sequence. There’s no rigid formula—but there is an important output: they have something to do while we review (often complex) procedures, and I have a record of who was paying attention. Left unchecked, middle schoolers have the approximate attention span of goldfish, so this tiny ritual pays outsized dividends once the activity begins.

In a world where most classrooms are 70% teacher talk (yes, that’s the actual number!) annotating directions helps us “steal” many more minutes back for the worthy work of digesting complex text.

“Mister!” 🙋🏽♂️

Kids can’t move on without my eye on their work, so you’d better believe they’re demanding my attention, often with the cartoonish urgency of a retriever who caught wind of the word “walk.”

This might seem arduous (especially for upper grade teachers used to “playing it cool,”) but that constant movement is actually a feature, not a bug. It keeps the room alive, and it keeps me on my toes, too. Every lap of the classroom tunes me into the work as it’s happening—the sticky spots that need whole-room clarity, the small imprecisions that need a push, and the flashes of creativity that deserve a quick doc-cam share.

And honestly? It’s really fun. The kids lose themselves in the moment. High fives, cheers, and fist bumps flow easily. They’re always surprised at how class went by in a flash, and they’re equally surprised by how much they got done.

It’s a massively efficient use of time.

The Virtuous Cycle 🔁

Grading classwork is an undeniable headache.

Nothing is more cliché than teachers marching cartons of papers to their cars on Friday afternoon—only to march them right back in on Monday morning, untouched.

The beauty of my manic packet-monitoring routine is that it doubles as grading. Once my mark is on the page, it’s done—and it earned a 100%. No extra hours. No stacks looming on the passenger seat.

Students get feedback in the moment that moves them to “proficient,” and the reward is immediate: a positive grade they already know before it ever hits the gradebook.

The system reinforces itself. Either you got your signatures, or you’ll get the assignment back to complete. There’s almost no in-between.

Once that becomes clear, the cycle feeds itself. Students stay on task, I stay present, and the packet handles most of the classroom management for me.

Losing the Room

All of this assumes paper is the organizing technology in the room. But when screens take over, the dynamics shift fast, even if the content stays the same.

Let’s look at two of the biggest obstacles teachers face when those same materials move online.

Supervision

In a classroom arranged in rows, you can see faces or screens—but never both. Cords snake through the aisles, making movement awkward, and every assignment is scrolled to a different spot, raising the “cost” for teachers of giving feedback face-to-face instead of staying tethered to their desk. The mechanics of managing class turn from “working together” into a game of whack-a-mole.

Efficiency, Feedback, and Cognitive Overload

Even when the tech works, the cognitive load is brutal. You’re tracking tabs, chasing visibility, and typing out notes that students might never read.

Meanwhile, students—tucked behind screens that they can dip and dim at will—simply feel less accountable. They produce less, need more reminders, and get far less feedback in the moment. The feedback loop collapses, and distractions creep in.

Sure, going digital saves some printing, sorting, and stapling. But if we care most about the student experience, the better tool is obvious.

A Worthy Sacrifice

At the end of the day, prioritizing paper takes both sacrifice and planning.

Stories of teachers squirreling away reams of copy paper in “times of plenty” are legion, and honorary certificates for copy machine whispering are owed to many. But despite the challenges, keeping text, attention and accountability at the center of the lesson makes the trade-offs seem small in comparison.

Plus, if you’re lucky, maybe that collection of pencil nubs will be worth something someday. 🤞🏻

When I see a teacher's thick packet (especially with a nice dose of Comic Sans), I see: love

I think of the hours the teacher put in, thinking ahead to how the students will respond, searching for images, and the hardest of all, fighting the formatting tools. Then after class, editing the packet to clarify, correct typos, adding more info.

This piece hits me right in the teacher soul. You perfectly captured that quiet magic of paper. What I love most is how you show that paper isn’t nostalgia. It’s literally pedagogy. The “virtous cycle” you describe is real: feedback, movement, mastery, joy.