Why Mastery Doesn't Matter

Our obsession with “standards mastery” has turned reading class into a slog for teachers and students — and it’s hiding an even bigger problem.

“A Matter of Equity”

“Take a moment,” the man urged, eyes boring into the crowd, “and write about your favorite teacher. What made their class special?”

It was the third day of Teach For America’s summer institute, and our instructor — a self-assured Harvard graduate, hardly further along in his teaching career than us — was enjoying himself.

Being the literacy team, we tore into the task with verve. We were, after all, high achievers who loved to read and write. Each of us had someone who pushed us, inspired us, made us feel at home — and we were here to be like them. I began to write about a high school teacher who introduced me to my favorite author, had us annotate our novels, dedicated whole blocks to Socratic discussion, and—

“Stop!” he interrupted. A wry grin crept across his face. “Now take that paper… and tear it in half.”

He stared us down from behind his podium as the sound of ripping paper filled the auditorium.

“What worked for you isn’t going to work for them. These kids,” he said pointedly, “need something different.”

The “different” that our kids needed, it turned out, was a rigorous focus on standards instruction. The theory, as he told it, was that our students had been underserved for their entire educational careers and lacked basic skills.

“It’s a matter of equity,” he solemnly explained. The argument was heavy, immune to retort.

Weeks of class spent immersed in full books, essays and discussions were for the privileged, he continued. We were here to teach skills. And if we didn’t like that, “a private school might be a better fit.”

The insinuation sent a collective chill through the room. We cast shameful glances at our torn papers, embarrassed by the blindness to our own privilege.

Those “missing skills,” laid out in the newly articulated state standards, were discernable, teachable, trackable, and testable. And we learned that just as a student could master multiplication and division, a student could also master the nuance of finding relevant details and applying them to determine a text’s main idea.

Once we helped our students master these skills, the possibilities for them were endless. This was the road map and the core mission, and it was accepted with a kind of religious zealotry. Our young trainer had done his job.

Over the next few weeks of summer school at my training site, the nine teenagers that had been placed under my care were subject to a clinical and regimented series of pre-tests, worksheets, quizzes, and reteaches. Wall charts were assembled and visions of smiley face stickers representing mastered reading skills-to-come crowded my mind as I wrote up lesson plans in my dorm room late into the night.

The pre-test revealed many opportunities for things to “master.”

23% on figurative language? A full-day lesson on similes should fix that.

“Say it with me again… ‘Like or as!’ — we’re getting there.”

“Main idea” only at 43%? No problem—fifteen more practice passages should do it.

Predictably, the summer I spent writing exhaustive explanations of what a “supporting detail” is and authoring inane quiz questions comparing the Arctic Circle to the school’s air conditioning unit (using “like” or “as,” of course) led nowhere. The class managed to regress on their post-test. Only 1 student met their goal.

On the long drive back to my regional site, I contemplated how my 9th grade year had been spent immersed in literature, writing complex essays, and exploring the worlds laid out by Steinbeck, Lee, Angelou and other influential thinkers. In contrast, the kids in my class hadn’t read a single thing...unless you counted the childish passages I was printing and assembling into packets in the library in the early hours of the morning.

Blessedly, great books and great mentors eventually guided me down a different path, but it was a long time before I was ready to hear it — and countless administrators and district leaders continued pushing the mastery gospel. As time went on, a simple truth became clear–the foundations of so many of our nation’s classrooms are built on an illusion.

In a secondary literacy classroom, the truth is this: mastery doesn’t matter. In fact, in many instances, it’s not even possible.

In a secondary literacy classroom, the truth is this: mastery doesn’t matter.

The Myth of Mastery

Consider the 6th grade Common Core Reading: Informational Text Standard 4 – “Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings.”

As an adult reader who likely has a college degree, your schema, fluency and experience shouldn’t make this a challenging task for virtually any middle school text.

But take the following sentence from this week’s “Times of India,” covering a cricket match:

Hope achieved his first Test hundred in eight years with a boundary off Mohammed Siraj but was soon dismissed when he dragged the ball onto his stumps.

If you are an American, the odds of complete befuddlement are high. You probably guessed at the meaning of “Test,” but the concept doesn’t translate to any sports that you are likely to be more familiar with, so your context is useless — you’d be guessing at best.

Does that mean you haven’t mastered a 6th grade skill? Of course not. But the only way you could accurately work through the sentence is with more background knowledge.

While the example is niche, the concept applies much more broadly. Even the most sophisticated adult reader of literature would fumble around with this month’s edition of JAMA, just as 6th graders with significantly below grade level reading skills can usually make easy meaning of The Diary of a Wimpy Kid.

Drilling, not Reading

So what’s the point? Nationwide, reading results are in the gutter. Most of our middle grade classrooms are spending the vast majority of their precious time with students on mindless activities that not only waste time, but also make school bleak and boring to endure. All of this erodes the student self-concept as a reader, with disastrous results for student learning and positive associations with reading.

As an example, take a look at this snippet from a workbook put out by Scholastic and linked to by a New Jersey School District as a “core resource.”

Anyone who has spent time in middle-grade classrooms in the last 20 years will recognize these types of activities in a heartbeat. They dominate “lesson starters” and “reteach stations,” while edtech platforms gamify them so students can keep “practicing” at home.

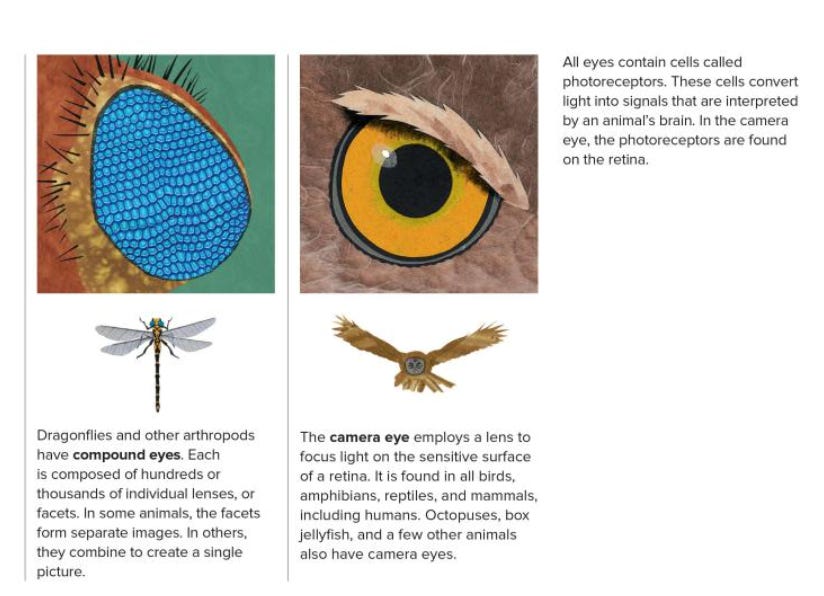

By contrast, consider this sample from the Caldecott-winning book, “Eye to Eye: How Animals See the World.”

Both samples fall in a Lexile range appropriate for upper elementary students (despite the extremely questionable marketing of the Scholastic book as “appropriate for grades 4-8.”)

In the world of text complexity, the Scholastic passage has its virtues. But despite whatever curiosities might be aroused in a student about planetoids, orbital patterns, telescope technologies or the scientific implications of “ancient ice,” students never get to visit the concepts again. There are 35 passages in the workbook, all on different topics, and none of which allow for instruction, building, or depth. It’s a veritable TikTok of reading instruction.

The second sample comes from a book on exactly one topic – eyes. The illustrations are precise, beautiful and enhance comprehension. There’s blank space for margin notes, observations, arrows and lists. Concepts like photoreceptors and retinas are not only complex and interesting, but they’re also explored in significant depth across the text. For example, the topic of how light is detected and processed by eyes to create images in the brain (or not, depending on the type of eye!) comes up 13 times over the course of the book. This gives students ample opportunities to utilize domain-specific vocabulary in context.

Can you imagine how much richer the inferences of a student writing about the differences between the image-forming pinhole eye of a clam and the light-detecting eyespot of a sea star become when they are operating with days of immersion and context-building? It’s vast.

Breaking the Spell

With more complexity and context comes higher-quality writing, which leads to more pride, engagement and joy in school. Teachers often feel the biggest boost.

Most of what I’ll write about in the future is what I (and what my most admired writers and thinkers) believe that teachers should do instead. But our collective desire for a “silver bullet” has led to an interpretation of how to get kids to the endpoint that is not only lazy, but tremendously damaging.

Just as early-elementary teachers are reckoning with the damage wrought by the dogma of ‘balanced literacy,’ our middle-grade classrooms must now confront—and urgently correct—the harm caused by our mastery-first obsession, especially for our most vulnerable students.

You might even say it’s a matter of equity.

Kenneth Goodman used to say, "A sentence is easier to read than a word. A paragraph is easier to read then a sentence. A story is easier to read than a paragraph. "

Reading the context of a mastery based classroom, we should look at the school as institution, and then public schools of poverty, and then eventual caste-based employment as the whole story. The people being schooled to work as interchangeable cogs are not meant to read the whole context. Excellent piece! Thank you!

Well done Luke! Keep going! You are spot on and will help change middle level education.