Wading Into the Deep End: What Reading Actually Requires When the Text Gets Hard

Explicit, text-driven modeling unlocks the rigor of complex texts. It's messy, and we should be doing far more of it.

“Mister, this is confusing. Is he like a robot zookeeper or something?”

The question made me blink, eyebrows involuntarily aloft.

It came after students had read a single sentence from Ray Bradbury’s A Sound of Thunder—a sentence I had assumed would spark curiosity, not confusion.

The activity, called Tea Party, was simple: students drew short snippets from an upcoming novel and, without further context, predicted what might happen next.

An example line from our opening novel, Freak the Mighty, might have been:

There are fair maidens to rescue, dragons to slay.

Expectedly, students invented a flurry of Arthurian scenarios, some surprisingly connected to the plot and others wildly off-base. One student was convinced Bowser (of Mario fame) would make an appearance. Groans followed; hands shot up. Wherever the discussion went, the activity reliably built anticipation and energy with our accessible texts.

By my third year, my ambitions had grown, and I tried the same strategy with more demanding prose.

Students once again pulled lines from a mystery envelope, this time from Bradbury’s time-traveling, Jurassic-era classic. The line in question described the time machine when the main character first encounters it:

“Eckels glanced across the vast office at a mass and tangle, a snaking and humming of wires and steel boxes, at an aurora that flickered now orange, now silver, now blue.”

My mistake was assuming that more sophisticated syntax would generate more sophisticated predictions. I imagined students speculating about the scientific nature of the aurora or the origins of the machine.

Instead, they offered ideas like:

“There’s gonna be snakes and Eckles is humming to them”

“Something exploded and lights are flickering everywhere”

And, in a district where fish was served on Fridays during Lent, at least one student concluded Eckels was “trippin” at Holy Mass.

“Interesting idea… but keep thinking about that,” became my refrain for the day.

What, I began to wonder, had gone so wrong?

Complexity as an Interaction

What I hadn’t yet realized was that nothing had gone “wrong” with the lesson—only with how I understood complexity itself.

My students—already hamstrung by the intentionally context-less task— didn’t understand many of the words as they were being used. Nearly every student avoided making a prediction about the aurora, for example, because almost none of them had encountered the word before. In other cases, familiar words like snaking appeared in unfamiliar roles, describing shape and motion rather than animals.

“Text complexity is not a property of the text alone, but of the interaction between the text, the reader, and the task.”

Timothy Shanahan

At first, I blamed the task and tried to fix it by releasing students into the text itself. Surely the preceding paragraphs would clarify things?

References to a “safari in the past,” hunting dinosaurs (obviously extinct), and a vocabulary list that included a definition of aurora should have anchored their understanding.

Except, it didn’t.

Students tripped just as hard over the sentence the second time as they had the first. If anything, the Mesozoic Mass had grown more troubling, and most students still hadn’t identified the time machine.

At the end of the day, I stared at a stack of mostly inane student writing, cycling through familiar questions:

Had I failed to differentiate enough?

Were my lessons on personification insufficient?

Did we just need another graphic organizer?

What I would eventually learn was that students didn’t lack effort or strategy. They lacked the schema to make meaning, and I had sent them to pasture—confusing withdrawal of support with rigor.

The only real remedy was a heavy dose of explicit instruction, grounded in the text itself.

How Schema Works in Real Reading

When I first learned about schema, I understood it as a loose collection of facts stored in one’s head. The idea that dinosaurs are extinct, for example, or that “time machines” are often depicted as overbuilt metal boxes that flash and bang, seemed like the relevant knowledge a reader might need to make sense of a sentence like Bradbury’s.

Over time, I’ve come to understand schema as something broader and more functional. It includes, among other things:

familiarity with how words behave across contexts

comfort with complex syntax

experience recognizing how authors signal a character’s inner state

In classrooms, schema is often discussed interchangeably with the more practical label of background knowledge. The terms aren’t identical, but they frequently function the same way. Background knowledge is the visible, teachable content that fills and activates schema—and without it, even careful rereading and close analysis have little to latch on to.

“There is no such thing as a fixed individual reading level; it’s going to depend on the topic that you’re reading about and how much you know about it.”

“Reteaching” Isn’t the Answer

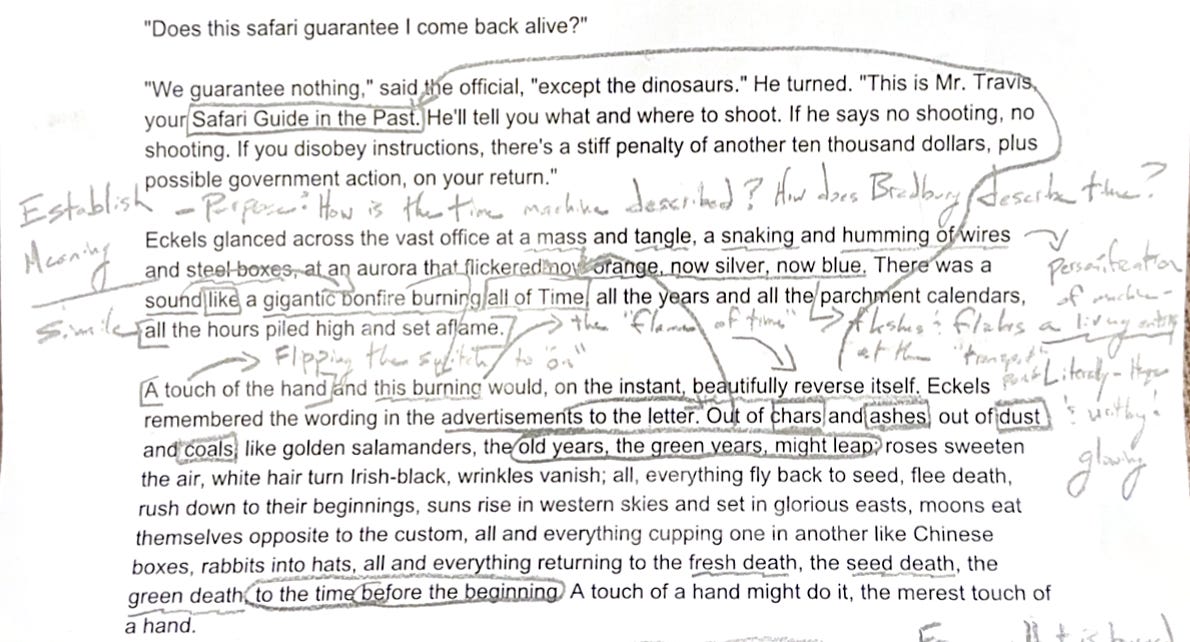

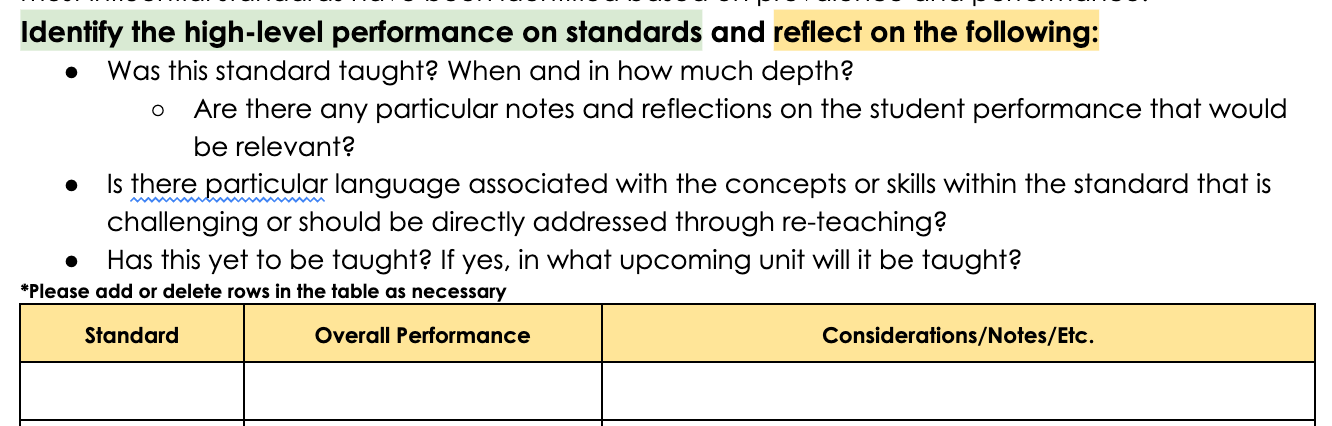

When schema is missing, instructional systems tend to misdiagnose the problem as a “skill” deficit—and nowhere is that clearer than in how student performance is interpreted.

Many schools use data analysis protocols that funnel student results toward evaluating standards mastery and planning a corresponding “reteach cycle.” The underlying assumption is clear: if students struggle with a text, they must be missing a discrete skill that can be identified, isolated, and taught again.

We can spend full class periods on reteaching standards, but what exactly are we reteaching?

Can you “reteach” Bradbury’s humanism? His kinetic imagery, his metaphorical lilt, his control of tone and consequence?

Of course not. Devoid of a source text, you can describe imagery. You can catalog metaphors. You can read a dozen examples of literary pivots.

But when students finally face the real thing, it often feels like trying to lift a heavy weight after weeks spent studying pictures of the barbells in the gym.

Writing is human, stylistic, emotive, and complex. The more it deviates from expectation, the more we tend to treat it as worthy of serious attention.

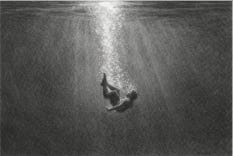

Instead of keeping students in the shallow end with decontextualized excerpts, a more effective approach is to immerse them—carefully—above their heads in real texts, and wade in with them to teach them how to swim.

The Art of Curated, Collective Reading

What I’m describing here is often called model reading, but it’s better understood as collective close reading—a shared act of meaning-making rather than a demonstration to be replicated.

As such, the process rests on two principles: curation and collectivity.

Curation

Not all text is worthy of collective close reading. Opening pages often are. Climactic moments, the launch of a new conflict, or key moments of character development almost always are. At the same time, students still need opportunities—and tools—to move through large swaths of a novel on their own.

A well-planned collective close read, then, functions like a lily pad in the larger pond of a novel’s rigor—an oasis where developing readers can climb out of the muck of independent meaning-making and get just-in-time practice with the next challenge ahead.

In Lord of the Flies, for example, students need a lily pad early on, during the first descriptions of the island, not because the setting is particularly confusing, but because the language is doing more than it first appears.

“Here the beach was interrupted abruptly by the square motif of the landscape; a great platform of pink granite thrust up uncompromisingly through forest and terrace and sand and lagoon to make a raised jetty four feet high.” (pg. 13)

A moment of intentional reading helps students not only grasp the island’s Eden-like beauty (and the sharp, predatory undertones that foreshadow what’s to come), but also learn how to read the metaphoric, allusion-heavy register Golding uses to shape both setting and, later, character.

“Go slow to go fast” may sound trite, but spending several days analyzing the elements of dystopia in the opening chapter of The Giver gives students the tools to unlock far more complex insights later—at the speed the author intends and with a high degree of independence.

“The trick is finding that fine balance between explicitly sharing the secrets of complex text with our students and instilling in them the cognitive patience, as Maryanne Wolf calls it, necessary to tap into those secrets for themselves.”

Too few lily pads in the pond and most swimmers drown; too many and they never grow stronger. Thoughtful curation—where supports appear, what tools are offered, and how far students must swim independently between them—pulls classrooms out of the tired “I do / we do / you do” progression and into something more responsive. Release is no longer gradual by default; it is modulated to the demands of the text itself.

Get the support cycles right, and students have the independence they need to tap into the text’s secrets on their own.

Collectivity

In real classrooms, student abilities are not neatly sorted into boxes. Even readers who test at similar levels often bring vastly different backgrounds, interests, and knowledge sets to the same text.

It’s commonly argued that these differences must be addressed primarily through differentiation. In practice, they’re more effectively bridged through thoughtful, explicit, collective instruction.

A few non-negotiables apply during a collective close read: every student has a paper copy of the text, a pencil in hand, and is accountable for recording the key ideas of the model and conversation in a predictable, checkable way. My strong preference is to capture those ideas live—on paper, under a document camera—so students can see my adult thinking unfold and record it alongside me.

From there, the teacher can drive collective engagement with a clear purpose (e.g. “How does the author signal mob mentality in this scene?”), while modeling fluent reading and rapidly clarifying the dozens of mini-lessons that even advanced readers need when they encounter something new.

These clarifications may be tangential to the day’s central question, but they’re no less essential to understanding the scene. As Carl Hendrick notes1, insufficient background knowledge can turn productive struggle into unproductive confusion—and it is precisely these small, in-the-moment distinctions that keep students in the former rather than the latter.

In this setting, adding techniques like cold calls and structured student talk don’t just increase participation—they allow the teacher to respond in real time to comprehension with the most important scenes in a text, while it is unfolding.

For example, a teacher might surface an inference from a confident reader, briefly test it through partner talk, and then ask a developing reader to summarize—responding to comprehension in real time rather than planning multiple parallel lessons.

And it only works when meaning is built together, grounded in the mess of text itself.

The Work That Lasts

So if we want to build more resilient readers, there are few better approaches than providing heavy, collective modeling in the moments that truly call for it.

Over time, those moments of deliberate practice become internalized. Students read with greater independence because they’ve repeatedly experienced what it feels like to wrestle with thorny text—and how to persist when meaning doesn’t come easy.

It is these residual effects—habits of attention, stamina, and confidence—that grant students not just access to the next text, but to a lifetime of reading.

So seed your lily pads generously throughout the pond—not only to help students face the deep, but to give you places to stand together, making meaning and finding pleasure in the work, before it’s time again for them to swim again on their own.

From Interleaving: A Short Guide

Great post! In my opinion, very helpful guidance for how to do this can be found in the book Robust Comprehension Instruction with Questioning the Author: 15 Years Smarter by Beck, McKeown, and Sandora. They discuss some caveats/cautions about modeling.

They write:

"Although there are many examples of modeling that work well, there are also some tendencies that reduce the potential impact of modeling as a teaching strategy. For example, attempts at predicting an obvious event, such as “I think the wolf is going to blow the third little pig’s house down,” do little to illustrate what is involved in figuring out ideas. This example points to a common problem in examples of modeling that we have seen, which is that what gets modeled tends to be the obvious. It also highlights the contrived nature of some kinds of modeling. In contrast, modeling when done well can help students “see” things in texts they might not have noticed and can allow students to observe or “overhear” how an expert thinks through a complicated idea. Which parts or ideas in a text that a teacher chooses to model are determined by the text ideas that the teacher thinks students might need help with, as well as by the teacher’s spontaneous reactions to text—yes, modeling should be reserved for what one has authentically noticed as a reader. Modeling should be as natural in character as possible. It should also be as brief as possible; a long soliloquy by the teacher is unlikely to effectively communicate key ideas to students."

You express this concisely when you refer to the benefit of modeling "in the moments that truly call for it".

"Did we just need another graphic organizer?" - Made me laugh out loud. Oh, the grail of the perfect organizer! I love how clearly you lay out just how immersed you need to be as a teacher to get students to really swim in complex texts. Maybe some would say it's messy work, but well-worth the outcomes.